Competition and Character Displacement

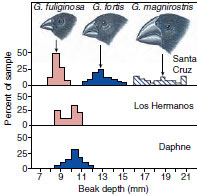

| Figure 40-8 Displacement of beak sizes in Darwin’s finches from the Galápagos Islands. Beak depths are given for the ground finches Geospiza fuliginosa and G. fortis where they occur together (sympatric) on Santa Cruz Island and where they occur alone on the islands Daphne and Los Hermanos. G. magnirostris is another large ground finch that lives on Santa Cruz. |

Competition occurs when two or more species share a limiting resource. Simply sharing food or space with another species does not produce competition unless the resource is in short supply relative to the needs of the species that share it. Thus, we cannot prove that competition occurs in nature based solely on the sharing of resources. However, we find evidence of competition by investigating the different ways that species exploit a resource.

Competing species may reduce conflict by reducing the overlap of their niches. Niche overlap is the portion of the niche’s resources shared by two or more species. For example, if two species of birds eat seeds of exactly the same size, competition eventually will exclude one species from the habitat. This example illustrates the principle of competitive exclusion: strongly competing species cannot coexist indefinitely. To coexist in the same habitat, species must specialize by partitioning a shared resource and using different portions of it. Specialization of this kind is called character displacement.

Character displacement usually appears as differences in organismal morphology or behavior related to exploitation of a resource. For example, in his classic study of the Galápagos finches, English ornithologist David Lack noticed that bill sizes of these birds depended on whether they occurred together on the same island (Figure 40-8). On the islands Daphne and Los Hermanos, where Geospiza fuliginosa and G. fortis occur separately and therefore do not compete with each other, bill sizes are nearly identical; on the island Santa Cruz, where both G. fuliginosa and G. fortis coexist, their bill sizes do not overlap. These results suggest resource partitioning, because bill size determines the size of seeds selected for food. Recent work by the American ornithologist Peter Grant has confirmed what Lack suspected: G. fuliginosa with its smaller bill selects smaller seeds than does G. fortis with its larger bill. Where the two species coexisted, competition between them led to evolutionary displacement of the bill sizes to diminish competition. An absence of competition today has been called appropriately “the ghost of competition past.”

|

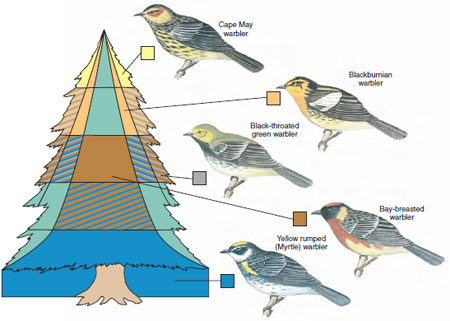

| Figure 40-9 Distribution of foraging effort among five species of wood warblers in a northeastern spruce forest. The warblers form a feeding guild. |

Guilds are not limited to birds. For example, a study done in England on insects associated with Scotch broom plants revealed nine different guilds of insects, including three species of stem miners, two gall-forming species, two that fed on seeds and five that fed on leaves. Another insect guild consists of three species of praying mantids that avoid both competition and predation by differing in sizes of their prey, timing of hatching, and height of vegetation in which they forage.