Linnaean Taxonomy

All species are classified in a ranked hierarchy, originally starting with kingdoms although domains have since been added as a rank above the kingdoms. Kingdoms are divided into phyla (singular: phylum) — for animals; the term division, used for plants and fungi, is equivalent to the rank of phylum (and the current International Code of Botanical Nomenclature allows the use of either term). Phyla (or divisions) are divided into classes, and they, in turn, into orders, families, genera (singular: genus), and species (singular: species).

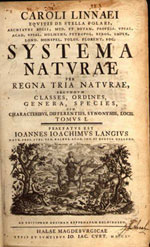

Though the Linnaean system has proven robust, expansion of knowledge has led to an expansion of the number of hierarchical levels within Title page of Systema Naturae, Halle an der Saale, Germany, 1760.

the system, increasing the administrative requirements of the system (see, for example, ICZN), though it remains the only extant working classification system at present that enjoys universal scientific acceptance. Among the later subdivisions that have arisen are such entities as phyla, superclasses, superorders, infraorders, families, superfamilies and tribes. Many of these extra hierarchical levels tend to arise in disciplines such as entomology, whose subject matter is replete with species requiring classification. Any biological field that is species rich, or which is subject to a revision of the state of current knowledge concerning those species and their relationships to each other, will inevitably make use of the additional hierarchical levels, particularly when fossil fo rms are integrated into classifications originally designed for extant living organisms, and when newer taxonomic tools such as cladistics and phylogenetic nomenclature are applied to facilitate this.

There are ranks below species: in zoology, subspecies and morph; in botany, variety (varietas) and form (forma). Many botanists now use "subspecies" instead of "variety" although the two are not, strictly speaking, of equivalent rank, and "form" has largely fallen out of use.

Groups of organisms at any of these ranks are called taxa (singular: taxon) or taxonomic groups.

Taxonomic ranks

| Taxanomic ranks | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Magnorder | ||||||||

| Domain / Superkingdom |

Superphylum / Superdivision |

Superclass | Superorder | Superfamily | Superspecies | |||

| Kingdom | Phylum/Division | Class | Legion | Order | Family | Tribe | Genus | Species |

| Subkingdom | Subphylum | Subclass | Cohort | Suborder | Subfamily | Subtribe | Subgenus | Subspecies |

| Infrakingdom/Branch | Infraphylum | Infraclass | Infraorder | Alliance | Infraspecies | |||

| Microphylum | Parvclass | Parvorder | ||||||

- Domain: Eukarya (organisms which have cells with a nucleus)

- Kingdom: Animalia (with eukaryotic cells having cell membrane but lacking cell wall, multicellular, heterotrophic)

- Phylum: Chordata (animals with a notochord, dorsal nerve cord, and pharyngeal gill slits, which may be vestigial or embryonic)

- Subphylum: Vertebrata (possessing a backbone, which may be cartilaginous, to protect the dorsal nerve cord)

- Class: Mammalia (endothermic vertebrates with hair and mammary glands which, in females, secrete milk to nourish young)

- Cohort: Placentalia (giving birth to live young after a full internal gestation period)

- Order: Primates (collar bone, eyes face forward, grasping hands with fingers)

- Suborder: Anthropoidea (monkeys, including apes, including humans; as opposed to the lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers)

- Infraorder: Catarrhini (Old World anthropoids)

- Superfamily: Hominoidea (apes, including humans)

- Family: Hominidae (great apes, including humans)

- Genus: Homo (humans and related extinct species)

- Species: Homo sapiens (high forehead, well-developed chin, gracile bone structure)

To view the complete classification of Kingdom: Plantae click here

Nomenclature

These rules are governed by formal codes of biological nomenclature. The rules governing the nomenclature and classification of plants and fungi are contained in the International Code of Botanical Nomenclature, maintained by the International Association for Plant Taxonomy. The current code, the "Saint Louis Code" was adopted in 1999 and supersedes the "Tokyo code". The corresponding code for animals is the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN), also last revised in 1999, and maintained by the International Commission on Zoological Nomenclature. The code for bacteria is the International Code of Nomenclature of Bacteria (ICNB), last revised in 1990, and maintained by the International Committee on Systematics of Prokaryotes (ICSP). There is also a code for virus nomenclature, the Universal Virus Database of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses (ICTVdB) although it is organized on somewhat different principles, as the evolutionary history of these forms is not understood.

Later developments since Linnaeus

Over time, our understanding of the relationships between living things has changed. Linnaeus could only base his scheme on the structural similarities of the different organisms. The greatest change was the widespread acceptance of evolution as the mechanism of biological diversity and species formation. It then became generally understood that classifications ought to reflect the phylogeny of organisms, by grouping each taxon so as to include the common ancestor of the group's members (and thus to avoid polyphyly). Such taxa may be either monophyletic (including all descendants) such as genus Homo, or paraphyletic (excluding some descendants), such as genus Australopithecus.Originally, Linnaeus established three kingdoms in his scheme, namely Plantae, Animalia and an additional group for minerals, which has long since been abandoned. Since then, various life forms have been moved into three new kingdoms: Monera, for prokaryotes (i.e., bacteria); Protista, for protozoans and most algae; and Fungi. This five kingdom scheme is still far from the phylogenetic ideal and has largely been supplanted in modern taxonomic work by a division into three domains: Bacteria and Archaea, which contain the prokaryotes, and Eukaryota, comprising the remaining forms. This change was precipitated by the discovery of the Archaea. These arrangements should not be seen as definitive. They are based on the genomes of the organisms; as knowledge on this increases, so will the categories change.

Reflecting truly evolutionary relationships, especially given the wide acceptance of cladistic methodology and numerous molecular phylogenies that have challenged long-accepted classifications, has proved problematic within the framework of Linnaean taxonomy. Therefore, some systematists have proposed a PhyloCode to replace it.

Quotations

"Taxonomy (the science of classification) is often undervalued as a glorified form of filing—with each species in its prescribed place in an album; but taxonomy is a fundamental and dynamic science, dedicated to exploring the causes of relationships and similarities among organisms. Classifications are theories about the basis of natural order, not dull catalogues compiled only to avoid chaos." Stephen Jay Gould (1990, p.98)Further reading on Linnaean Taxonomy

- Dawkins, Richard. 2004. The Ancestor's Tale: A Pilgrimage to the Dawn of Life. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Ereshefsky, Marc. 2000. The Poverty of the Linnaean Hierarchy: A Philosophical Study of Biological Taxonomy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gould, Stephen Jay. 1989. Wonderful Life: The Burgess Shale and the Nature of History. W. W. Norton & Co.

- Pavord, Anna. The Naming of Names: The Search for Order in the World of Plants. Bloomsbury.