Uses Of Monitor Lizards by Man

Mankind uses monitor lizards in a number of ways; for food, as pest controllers and to make drugs and leather. In some parts of the world they are of enormous economic importance, but in a few places they are considered a menace and efforts made to obliterate them.The diets of many monitor lizards make them ideal pest controllers, and their use as such is undoubtedly their most valuable property. They eat crocodile eggs and venomous snakes as well as huge amounts of crop-damaging crabs, snails, beetles and orthopterans. In many parts of Africa and Asia they are encouraged to inhabit paddy fields, coconut groves and other farmland to reduce crop damage (e.g. Deraniyagala 1931). Rosenberg's goanna may have been introduced to many islands off South Australia to reduce the numbers of venomous snakes and the World Health Organisation considered introducing the mangrove monitor to rat-infested islands in the Pacific until its decided preference for crabs became apparent (Uchida 1967). The few studies conducted on monitor lizards living in agricultural areas have all indicated that their diets consist largely of animals that are injurious to crops (Auffenberg et al 1991, Traeholt 1993, Bennett & Akonnor 1995) and in many areas their habit of consuming carrion is approved of. Where monitor lizards are not persecuted they will live close to (or even within) human settlements, foraging around rubbish dumps and feeding on all manner of debris. They are a common sight around some of the largest cities in Africa, Asia and Australia and are presumably tolerated because they help to reduce the amount of food for rats, flies and other urban pests.

The juicy flesh of monitor lizards has long been appreciated. It is rich in fat and can be roasted, grilled, smoked stewed, curried or fried. If cooked carefully, it is tender and not in the least stringy or tough. The choice cuts are the liver, the base of the tail and the eggs. Cochran (1930) reports that the eggs of water monitors were considered suitable for presentation to the King of Thailand. Followers of Islam in Asia will not eat monitor lizards, but many devout Muslims in West Africa consider them a great delicacy. In some parts of the Philippine Islands water monitors are a major food item and in many parts of the world they are used to augment pitifully small protein intakes. Their use as food throughout Africa, Asia and Australia appears to be widespread (e.g. Irvine 1969). The mangrove monitor has been introduced to many islands in the Pacific within living memory, possibly as a food source.

A bewildering array of tonics, medicines and potions are made from various parts of the monitor lizards' anatomies (e.g. Gaddow 1901, Auffenberg 1982, Das 1989 and references cited therein). The fat is used to treat deteriorating eyesight and for a variety of other ailments (particularly arthritis, rheumatism, piles and muscular pains). It is also used as a sexual lubricant (Saxena 1993). Dried gall bladders are particularly therapeutic, curing heart problems, impotency and liver failure as well as a number of more serious complaints. In North Africa dried heads of monitor lizards are sold to be pulverised and used for the treatment of various external and internal afflictions (Linley, pers.comm.). Amnesiacs in Sri Lanka sometimes prepare a meal of monitor lizard tongues, which is said to restore the memory to its full capacity (de Silva, pers.comm). Krishnan (1992) reports that a man who had sustained a serious thigh wound as the result of an encounter with a wild boar was treated by his friends in the following manner: Thin slices of fresh, Bengal monitor flesh were inserted into the deep wound , which was then bandaged up. The man later claimed that the wound had healed completely within ten days and exhibited a "surprisingly small" scar. As far as I am aware none of the monitors' therapeutic properties have yet been subjected to serious scrutiny. In Sri Lanka it was also believed that a mixture of water monitor fat and flesh and human blood and hair makes a very strong poison when boiled, and that a drop is sufficient to cause the instant death of an enemy (Auffenberg 1982). Water monitors were also said to ne instrumental in the preparation of the Singalese assassins' most favoured poison, kabaratel. The raw ingredients (fresh snake venom, arsenic and various herbs) were mixed with water in a human skull and placed on a fire, at three corners of which bound water monitors were strategically placed and beaten. so that their hisses would hasten the boiling process and add to the strength of the concoction. The froth from the lizards' lips was added at the last minute. And when an oily scum rose to the surface the dreadful potion was complete (Morris in Gaddow 1901).

According to Das (1988), killing monitor lizards with rakes is a form of sport in parts of northeastern India. Similarly, children in parts of the Kara-Khum desert take great delight in seeking out Caspian monitors and bludgeoning them to death. Because the lizards are believed to be venomous, participation and success in this sport is considered to be an act of great bravery (pers. obs.).

The ingenious ann renown Mararathi warrior Karna Singh breached the walls of the Fort of Kelna by tying a rope to a monitor lizard, allowing it to scale the wall and following it up when it had secured itself in a tight crevice. Thereafter his tribe were known as Ghorpade (after the Marathi name for the Bengal monitor. ghorpad) and every soldier in the army was trained in their use (Ramakrishna 1983). Less heroic individuals used the lizards to climb the walls of houses they were burgling (Robinson in Gaddow 1901).

A number of cultures were said to allow monitor lizards to feed on their deceased relatives and thus eliminated the need to dispose of corpses by burying or burning them. In the Mergui Archipelago corpses were left on exposed platforms in the forest whilst on Bali the bodies were covered with wicker baskets that kept dogs and monkeys out and allowed the lizards to feed in peace (Anderson 1889, Auffenberg 1982). Such free and nutritious meals attracted large numbers of water monitors. Anderson reports that up to 15 specimens were seen "engaged in a ghastly meal of this kind".

By far the most conspicuous use of monitor lizards is for their skins. Traditionally used for drumheads and shields, monitor skins are in great demand in the richer parts of the world to make watchstraps, shoes, wallets, handbags and other leather goods. The exquisite patterns of the lizards combined with the durability of their hides make them the most popular family of lizards in the skin trade. Most are caught in the poorer countries of central Africa and South East Asia and are sold in Europe, North America and Japan. As far as I am aware there is no demand for monitor lizard meat in Europe, nor are the gall bladders widely available, so the demand for the animals comes only from the fashion market The numbers of animals involved in the trade is vast and the reported numbers may represent only a small proportion of the actual trade. Until 1975 there was no international attempt to monitor the number of lizard skins shipped from country to country. but there is no doubt that in many areas a flourishing export trade has existed for well over a hundred years. Mertens (1942a) suggested that the Second World War was beneficial to monitor lizards, by providing them with some respite from intensive exploitation.

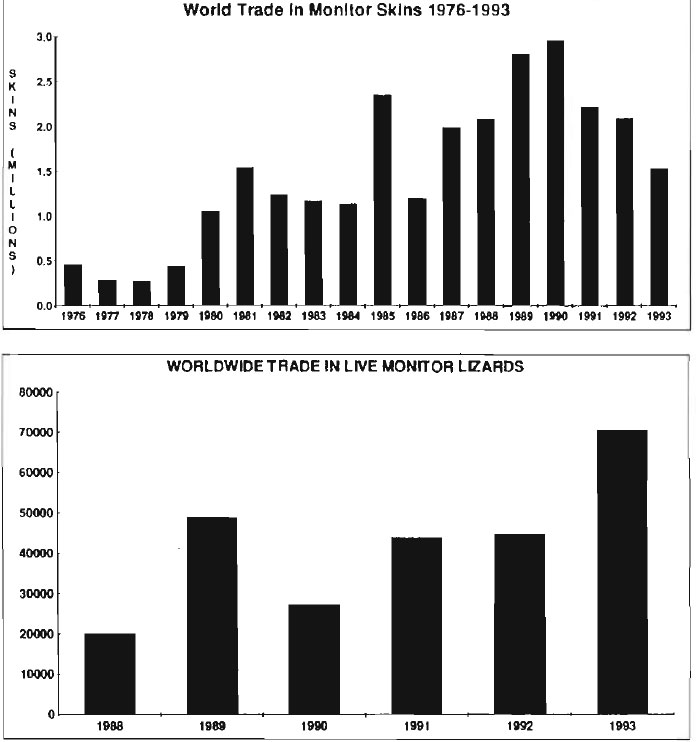

In 1973-74 Ihe Bangladeshi Government estimated that exports of lizard skin were worth more than US$1,300,000 (Gilmour 1984). Reported trade in lizards skins from India between 1964 and 1973 was over 2.5 million kg. valued at almost 15 million rupees (Anon 1978). However trade reported to CITES during 1975 amounted to only 51.239 skins. of which 38,478 originated in the Indian subcontinent. Minimum net trade in monilor lizard skins from 1975- 1993 are shown below. The significant rise in numbers between the late 1970's and the early 80's is more likely to be a reflection of the increasing efficiency of the reporting syslem rather than a true indication of a rise in demand . Figures for 1993 are incomplete.

|

| (Sources: CITES trade statistics derived from the WCMC CITES trade database. WCMC, Cambridge. Luxmoore et al 1988. Luxmoore & Groombridge 1990. Jenkins & Broad 1994) |

Not all monitor lizards are exploilted for their skins in fact the brunt of the trade is borne by just five or six species. The watler monitor (V.Salvator) is the most heavily collected species, with trade in almost 2.5 million skins reported in 1990 alone. The major exporters of water monitor skins are Indonesia, the Philippines and Thailand. Most skins are shipped through Singapore and find markets throughout the rest of eastern Asia, Europe and North America. In Africa the Nile monitor is the most heavily exploited species with average trade in over 400,000 skins reported between 1980 and 1985. Most skins are exported from Nigeria, Sudan, Mali and Cameroon and are sold in France, Italy and the U.S.A. Large scale trade in V.exanthematicus (i .e. V.albigularis and V.exanthematicus) is also reported. with an average of 88,000 skins shipped each year between 1980 and 1985. Most of these animals originated in Nigeria (V.exanthimaticus) and, to a lesser extent. Mali (V.exanthematicus). Sudan (?) and South Africa (V.albhigularis). Most of the demand comes from France, other European nations and the USA .. Trade in the skins of desert monitors. V.griseus, is often reported, but according to Auffenberg (1982) its skin is too thin to make good leather and it is considered a very poor substitute for other monitor skins. Most animal skins traded as V.griseus probably belong to the two completely protected species V.bengalensis and V flavescens. Commercial trade in these species has been outlawed since 1975, but several countries. notably Japan , ignored the ban and continued to import large quantities of their skins until very recently. Between 1983 and 1986 over one million V.bengalensis skins were traded, mainly from India, Bangladesh and Thailand and almost all being exported to Japan. Trade in V.flavescens skins amounted to an average of almost 120,000 skins per year between 1983 and 1986). Almost all the skins originated in India and Bangladesh and again Japan was by far the largest consumer. It should be noted that all of the figures cited above refer to whole skins only, and do not include products made from monitor lizards or transactions reported by weight (often amounting to thousands of kilogrammes per year). Nor do they include over 1.5 million skins registered by Japanese customs between 1983 and 1987 but not declared to CITES. Furthermore Varanus skins are frequently misidentified in official declarations, with Asian species exported from African countries and vice versa. Exporters must find it very easy to deceive customs and CITES officials. During my investigations several Customs offices in several countries requested photographs depicting the various species, admitting they were unable to tell the difference between them. The most recent report of worldwide trade in reptile skins (Jenkins & Broad 1994) includes a single photograph of "V.saivator", the most frequently encountered monitor in the skin trade, which is clearly misidentified and should have been labelled V.dumerilii, a species in which leather trade is unknown!

The exploitation of monitor lizards has largely been overlooked by Westerners. Most people do not consider monitor lizards to be cuddly animals and perhaps it is on account of their lack of fur that their slaughter does not incur the sympathy extended to other victims of the leather trade. As far as is known, not a single monitor lizard has been bred commercially and so the trade relies entirely on animals taken from the wild. Considering the vast numbers involved and the fact that only the skins of adults or subadults are suitable it can be presumed that the trade will eventually deplete numbers to the point that they become extinct in many areas. Recent large-scale extinctions have been suggested for several monitor lizards in Pakistan, India and Bangladesh but it is unclear whether their demise is attributable more to direct human predation than to habitat destruction. Studies of heavily exploited populations in Sumatra revealed some of the highest biomasses recorded for any lizard in the world (Erdelen 1988, 1991) and there are no clear cases of monitor populations being decimated in any part of South-East Asia or Africa because of the activities of the skin trade. Habitat destruction, on the other hand, can be held responsible for reduction in monitor lizard numbers in all countries in which they occur. It is difficult to think of the skin trade without revulsion, but the poverty in Africa and Southeast Asia is much more unpalatable. The potential of monitor lizards as a very profitable and sustainable resource must have occurred to many people, but no serious attempts at farming them on a commercial scale appear to have been made. This may be due to the fact that they are still abundant in many areas, but if mankind is to continue to benefit from monitor lizards far into the future large scale captive breeding will be obligatory.

Some well meaning but misinformed people condemn eating monitor lizards on the basis not of taste, but of morality. They consider that using them for food (or indeed for any purpose) contributes to their demise, but fail to appreciate that almost all of the countries where monitor lizards occur are unimaginably poorer than anywhere in North America or Europe. Because they have very little money they experience very high infant mortality and very low life expectancy. This forces them to adopt unsustainable economic practises that result in the destruction of local ecosystems, the extinction of many animals and plants and land fit for nothing but shanty-towns and refugee camps. Of all wild animals, monitor lizards are among the best suited to sustainable use. They breed and grow very quickly and many are equally happy living in pristine forest, a field of corn or a rubbish dump. They quickly establish large populations wherever adequate food is available and they are not fussy about their diets. Their flesh is extremely nutritious and most importantly, their skins are very valuable. The price of a pair of monitor lizard shoes in Italy or Japan would feed a family for a year in most parts of the world. Westerners who object to the use of any animal skins except those of cows and sheep often fail to appreciate that animals with no economic value are likely to find their right to existence questioned increasingly as the populations of poorer countries burgeon.

Attribution / Courtesy: Daniel Bennett. 1995. A Little Book of Monitor Lizards. Viper Press U.K.