Classification and Phylogeny of Animals

|

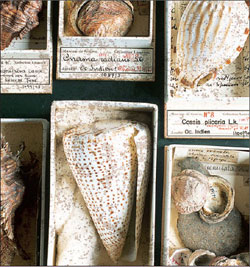

| Molluscan shells from the collection of Jean Baptiste de Lamarck (1744 to 1829). |

Zoologists have named more than 1.5 million species of animals, and thousands more are described each year. Some zoologists estimate that the species named so far constitute less than 20% of all living animals and less than 1% of all those that have existed in the past.

Despite its magnitude, the diversity of animals is not without limits. There are many conceivable forms that do not exist in nature as our myths of minotaurs and winged horses demonstrate. Characteristic features of humans and cattle never occur together in nature as they do in the mythical minotaur. Nor do characteristic wings of birds and bodies of horses occur naturally as they do in the mythical horse, Pegasus. Humans, cattle, birds, and horses are distinct groups of animals, yet they do share some important features, including vertebrae and homeothermy, that separate them from even more dissimilar forms such as insects and flatworms.

All human cultures classify their familiar animals according to various patterns in animal diversity. These classifications have many purposes. Animals may be classified in some societies according to their usefulness or destructiveness to human endeavors. Others may group animals according to their roles in mythology. Biologists group animals according to their evolutionary relationships as revealed by ordered patterns in their sharing of homologous features. This classification is called a “natural system” because it reflects relationships that exist among animals in nature, outside the context of human activity. Systematic zoologists have three major goals: to discover all species of animals, to reconstruct their evolutionary relationships, and then to classify them accordingly.

Darwin’s theory of common descent (Life: Biological Principles and the Science of Zoology) is the underlying principle that guides our search for order in the diversity of animal life. Our science of taxonomy (“arrangement law”) produces a formal system for naming and classifying species that reflects this order. Animals that have very recent common ancestry share many features in common and are grouped most closely in our taxonomic classification; dissimilar animals that share only very ancient common ancestry are placed in different taxonomic groups except at the “highest” or most inclusive levels of taxonomy. Taxonomy is part of the broader science of systematics, or comparative biology, in which everything that is known about animals is used to understand their evolutionary relationships. The study of taxonomy predates evolutionary biology, however, and many taxonomic practices are remnants of a pre-evolutionary world view. Adjusting our taxonomic system to accommodate evolution has produced many problems and controversies. Taxonomy has reached an unusually active and controversial point in its development in which several alternative taxonomic systems are competing for use. To understand this controversy, it is necessary first to review the history of animal taxonomy.