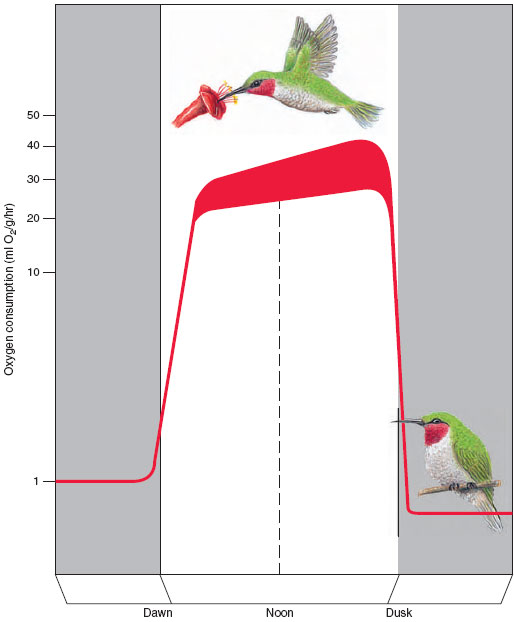

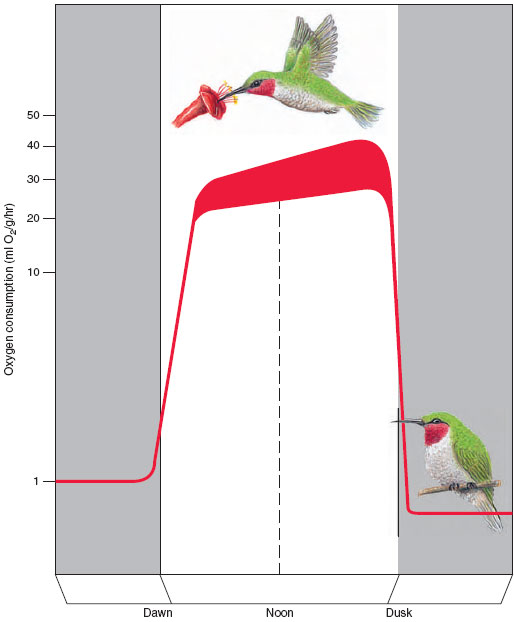

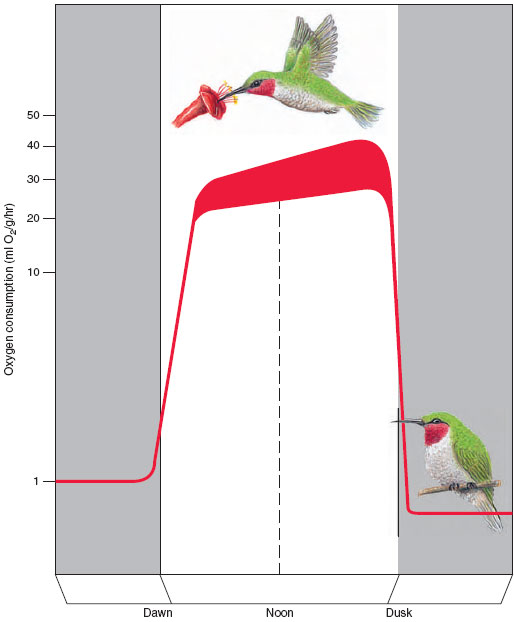

Figure 32-20 Torpor in hummingbirds. Body temperature and oxygen consumption (red line) are high when hummingbirds are active during the day but may drop to one-twentieth these levels during periods of food shortage. Torpor vastly lowers demands on the bird’s limited energy reserves.

Endothermy is energetically expensive. Whereas an ectotherm can survive for weeks in a cold environment without eating, an endotherm must always have energy resources to supply its high metabolic rate. The problem is especially acute for small birds and mammals which, because of their intense metabolism, may require a daily intake of food each day approaching their own body weight to maintain homeothermy (food consumption by birds is related on, and by mammals on . It is not surprising then that a few small birds and mammals have evolved ways to abandon homeothermy for periods ranging from a few hours to several months, allowing their body temperature to fall until it approaches or equals the temperature of surrounding air.

Figure 32-20 Torpor in hummingbirds. Body temperature and oxygen consumption (red line) are high when hummingbirds are active during the day but may drop to one-twentieth these levels during periods of food shortage. Torpor vastly lowers demands on the bird’s limited energy reserves.

Some very small mammals, such as bats, maintain high body temperatures when active but allow their body temperature to drop profoundly when inactive and asleep. This is called daily torpor, an adaptive hypothermia that provides enormous saving of energy to small endotherms that are never more than a few hours away from starvation at normal body temperatures. Hummingbirds also may drop their body temperature at night when food supplies are low (Figure 32-20).

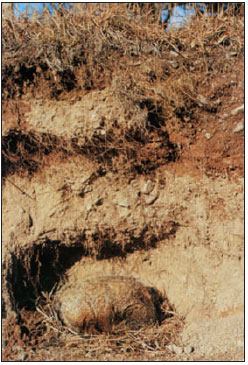

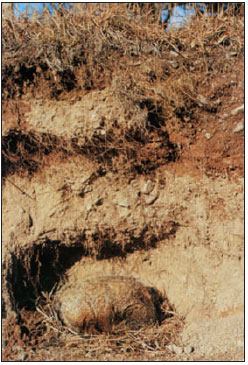

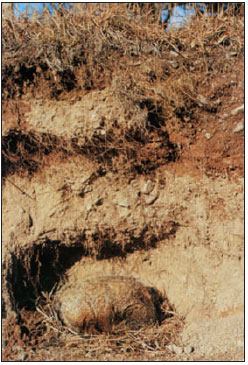

Figure 32-21 Hibernating woodchuck Marmota monax (order Rodentia) in den exposed by road-building work sleeps on, unaware of the intrusion. Woodchucks begin hibernating in late September while the weathe r is still warm and may sleep six months. The animal is rigid and decidedly cold to the touch. Breathing is imperceptible, as slow as one breath every five minutes. Although it appears to be dead, it will awaken if the den temperature drops dangerously low.

Many small and medium-sized mammals in northern temperate regions solve the problem of winter scarcity of food and low temperature by entering a prolonged and controlled state of dormancy: hibernation. True hibernators, such as ground squirrels, jumping mice, marmots, and woodchucks (Figure 32-21), prepare for hibernation by storing body fat. Entry into hibernation is gradual. After a series of “test drops” during which body temperature decreases a few degrees and then returns to normal, the animal cools to within a degree or less of the ambient temperature. Metabolism decreases to a fraction of normal. In ground squirrels, for example, the respiratory rate decreases from a normal rate of 200 per minute to 4 or 5 per minute, and the heart rate from 150 to 5 beats per minute. During arousal a hibernator both shivers violently and employs nonshivering thermogenesis to produce heat.

Figure 32-21 Hibernating woodchuck Marmota monax (order Rodentia) in den exposed by road-building work sleeps on, unaware of the intrusion. Woodchucks begin hibernating in late September while the weathe r is still warm and may sleep six months. The animal is rigid and decidedly cold to the touch. Breathing is imperceptible, as slow as one breath every five minutes. Although it appears to be dead, it will awaken if the den temperature drops dangerously low.

Some mammals, such as bears, badgers, raccoons, and opossums, enter a state of prolonged sleep in winter with little or no decrease in body temperature. Prolonged sleep is not true hibernation. Bears of the northern forest sleep for several months. A bear’s heart rate may decrease from 40 to 10 beats per minute, but body temperature remains normal and the bear is awakened if sufficiently disturbed. One intrepid but reckless biologist narrowly escaped injury when he crawled into a den and attempted to measure the bear’s rectal temperature with a thermometer!