The Dorsal Vertebra

The first dorsal vertebra is defined as such, by the union of its ribs with the sternum by means of a sternal rib; which not only, as in the Crocodilia, becomes articulated with the vertebral rib, but is converted into complete bone, and is connected by a true articulation with the margin of the sternum.The number of the dorsal vertebrae (reckoning under tnat head all the vertebrae, after the first dorsal, which possess distinct ribs, whether they be fixed or free) varies. The centra of the dorsal vertebrae either possess cylindroidal articular faces, like those of the neck, as is usually the case; or, more or fewer of them may have these faces spheroidal, as in the Penguins. In this case, the convex face is anterior, the concave, posterior. They may, or may not, develop inferior median processes. They usually possess well-marked spinous processes. Sometimes they are slightly movable upon one another; sometimes they become anchylosed together into a solid mass.

It is characteristic of the dorsal vertebrae of Birds that the posterior, no less than the anterior, vertebrae present a facet, or small process, on the body, or the lower part of the arch, of the vertebra for the capitulum of the rib, while the tipper part of the neural arch gives off a more elongated transverse process for the tuberculum. Thus the transverse processes of all the dorsal vertebrae of a bird resemble those of the two anterior dorsals of a crocodile, and no part of the vertebral column of a bird presents transverse processes with a step for head of the rib, like those of the great majority of the vertebrae of Crocodilia, Dinosauria, Dicynodontia, and Pterosauria.

The discrimination of the proper lumbar, saoral, and anterior caudal vertebrae, in the anchylosed mass which constitutes the so-called "sacrum" of a bird, is a matter of considerable difficulty. The general arrangement is as follows: The most anterior lumbar vertebra has a broad transverse process, which corresponds in form and position with the tubercular transverse process of the last dorsal. In the succeeding lumbar vertebrae this process extends downward; and, in the hindermost, it is continued from the centrum, as well as from the arch of the vertebra, and forms a broad mass which abuts against the ilium. (It would be more proper to say that ossification extends into it from the centrum as well as from tne neural arch. The process, like other processes, exists before the centrum is differentiated from the arch by ossifioation.) This process might well be taken for a sacral rib, and its vertebra for the proper sacral vertebra. But, in the first place, I find no distinct ossification in it; and, secondly, the nerves which issue from the intervertebral foramina in front of and behind this vertebra enter into the lumbar plexus, which gives origin to the crural and obturator nerves, and not into the sacral plexus, which is the product of the nerves which issue from the intervertebral foramina of the proper sacral vertebrae in other Vertebrata. Behind the last lumbar vertebra follow, at most, five vertebrae, which have no ribs, but their arches give off horizontal, lamellar, transverse processes, which unite with the ilia. The nerves which issue from the intervertebral foramina of these vertebrae unite to form the sacral plexus, whence the great sciatic nerve is given off; and I take them to be the homologues of the sacral vertebra of Reptilia. The deep fossae between the centra of these vertebrae, their transverse processes, and the ilia, are occupied by the middle lobes of the kidneys.

If these be the true sacral vertebrae, it follows that their successors are anterior caudal. They have expanded upper transverse processes, like the proper sacral vertebrae; but, in addition, three or four of the most anterior of these vertebrae possess ribs which, like the proper sacral ribs of reptiles, are suturally united, or anchylosed, proximally, with both the neural arches and the centra of their vertebrae, while, distally, they expand and abut against the ilium. The anchylosed caudal vertebrae may be distinguished as urosacral. The caudal vertebrae which succeed these may be numerous and all distinct from one another, as in Archaeopteryx and Rhea; but, more generally, only the anterior caudal vertebrae are distinct and movable, the rest being anchylosed into a plough-share shaped bone, or pygostyle, which supports the tail-feathers and the uropygial gland, and sometimes, as in the Woodpeckers and many other birds, expands below into a broad polygonal disk.

The centra of the movable presacral vertebrae of Birds are connected together by fibro-cartilaginous rings, which extend from the circumference of one to that of the next. Each ring is continued inward into a disk with free anterior and posterior faces-the meniscus. The meniscus thins toward its centre, which is always perforated. The synovial space between any two centra is, therefore, divided by the meniscus into two very narrow chambers, which communicate by the aperture of the meniscus. Sometimes the meniscus is reduced to a rudiment; while, in other cases, it may be united, more or less extensively, with the faces of the centra of the vertebrae. In the caudal region, the union is complete, and the meniscus altogether resembles an ordinary intervertebral cartilage.

A ligament traverses the centre of the aperture in the meniscus; and, in the chick, contains the intervertebral portion of the notochord. As Jager ("Das Wirbelkorpergelenk der Vogel." Sitzungsberichte der Wienel Akademic, 1858.) has shown, it is the homologue of the odontoid ligament in the cranio-spinal articulation; and of the pulpy central part of the intervertebral fibrocartilages in Mammalia.

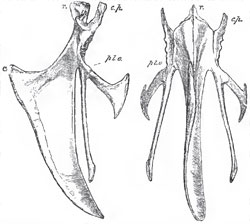

All the vertebral ribs in the dorsal region, except, perhaps, the very last free ribs, have widely-separated capitula and tubercula. More or fewer have well-ossified uncinate processes attached to their posterior margins, as in the Crocodilia. The vertebral ribs are completely ossified up to their junction with the sternal ribs. The sternum, in birds, is a broad plate of cartilage, which is always more or less completely replaced in the adult by membrane-bone.(These statements respecting the vertebral column, ribs, and sternum, like those further on toucning the skull, do not apply to Archaopteryx, in which all these parts are unknown or imperfectly known.) It begins to ossify by at fewest, two centres, one on each side, as in the Ratitae. In the Carinatae it usually begins to ossify by five centres, of which one is median for the keel, and two are in pairs, for the lateral parts of the sternum. Thus the sternum of a chicken is at one time separable into five distinct bones, of which the central keel-bearing ossification (r. to m. x. in Fig. 81) is termed the lophosteon, the antero-lateral piece which articulates with the ribs, pleurosteon (pl. o.), and the posterolateral bifurcated piece, metosteon.

The extent to which the keel of the lophostcon is developed in the carinate birds varies very much. In Strigops it is rudimentary; in birds of powerful flight, as well as in those which use their wings for swimming, it is exceedingly large.